Editor’s Note: As students around the country process recent incidents of racial violence, educators are working to create a safe space to address it. Teacher Colin Pierce describes how one lesson, inspired by Marvin Gaye and Nikki Giovanni, made an unexpected impact in a community discussion.

“I’m scared,” Will’s sister said. “I’m scared for him because I think, ‘What if he has a run-in with the police? What will that officer see and how will he react?'”

She blinked and two big tears rolled down her cheeks. She looked over at her brother, a tall, sweet-faced, linebacker of a sophomore at my school. He, too, sniffed and began swiping the tears away from his eyes. Soon it was his mother, then the stranger next to her, then nearly everyone in the room.

In a school community composed of nearly 95 percent students of color, in a neighborhood that has a higher rate of gun violence than anyone would like, this lesson was also designed as a forum to discuss the fears and anxieties stirred up by this year’s seemingly endless string of black and brown men and women killed or assaulted by police, vigilantes and, more recently, racially motivated domestic terrorists.

What emerged was a conversation highlighting a truth that is often lost amid the sensational headlines and commentary on what might justify the taking of a life.

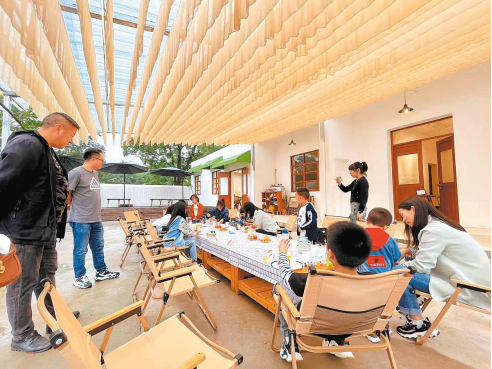

This happened at one of the monthly community outreach events that my colleague Cambrie Nelson and I have been organizing for the past few years. We rotate these events through community centers and other neighborhood gathering places to bring sample lessons to parents and the broader community, with the goal of building supports that enable our largely low-income student population to engage and succeed in the challenging International Baccalaureate (IB) Program.

That day featured a Language Arts lesson aimed at developing comparative textual analysis skills and looking at the way the cultural and historical context of authors and audiences can shape the meaning of a text. I had paired Marvin Gaye’s song “What’s Going On” with the Nikki Giovanni poem “We” and asked the participants to reflect on the messages of each, and then how those messages might have different meaning for young people today.

When I planned the lesson out the day before, I didn’t intend it to end with everyone crying in the basement of a church. And yet there we were, all of us gathered around a table on a rainy Seattle Saturday, with tears streaking our cheeks.

What is really at stake when we talk about systemic violence against black and brown bodies is the psychological and physical survival of thoughtful, caring, young people like Will and the collateral damage of trauma inflicted on sisters, mothers, fathers and brothers. Will is loved fiercely by his family and his community, and he deserves, as all young people do, to have that love expressed more frequently as celebration than as constant fear for his life.

I am white, raised in an affluent neighborhood in Oakland, California, and it would be insulting for me to presume I have anything to teach my students and their families about the experience of racial or economic injustice. But as a teacher in their community school, it is my obligation to create space and resources for those conversations to happen. It is my obligation to make sure the central concerns of the community I serve have a respected place in my class and curriculum.

As my school and others like it work to bring high-quality learning like the IB program to students frequently denied access, we must recognize that we cannot do this successfully without incorporating their families, communities and contexts into their education.

The outreach events started with me “talking to a box of cookies in an empty room,” as the Seattle Times recently pointed out, but we now regularly get over 60 participants. The meetings are part of a larger effort by the exceptional staff and parent body of our school that has seen increases in graduation rates, student achievement and participation in challenging courses.

Our students are already in many ways sophisticated readers of the world around them and we stand the best chance of further developing and transferring those strengths into their school lives when we provide them with content that is relevant to the events and ideas that loom large in their lives. When we do, the conversations in our classrooms spill out into our students’ homes and the communities surrounding them. They now have the tools to be powerful leaders and advocates when they find themselves, their families and their communities under threat.

Sitting around the table that Saturday afternoon, no one tried to interrupt the mood with comforting platitudes. They weren’t necessary. It was enough for the time being to simply be together, sharing our fears and aspirations for our young people and the future of our community, and to hope we could help keep Will and his classmates safe long enough to develop into the agents of change we know they are capable of becoming.

Colin Pierce is a language arts teacher and IB diploma program coordinator at Rainier Beach in Seattle, Washington.

Popular News

Current News

Manufacturing

Collaboratively administrate empowered markets via plug-and-play networks. Dynamically procrastinate B2C users after installed base benefits. Dramatically visualize customer directed convergence without

Collaboratively administrate empowered markets via plug-and-play networks. Dynamically procrastinate B2C users after installed base benefits. Dramatically visualize customer directed convergence without revolutionary ROI.

About Us

Tech Photos