Editor’s note: Today’s Teachers’ Lounge features several perspectives by educators on the issue of school shootings in the U.S.

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow

by Anthony Lodato, English teacher at Montville Township High School in Montville, New Jersey

We were supposed to cover Macbeth today. Our focus should have been the “Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow” speech. This is Macbeth’s soliloquy about time, death and meaninglessness. We instead had a conversation that, sadly, will need to be repeated tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow.

Just like our nation, the class has to discuss the heart-wrenching topic of school violence and mass shootings. And it won’t be the last conversation.

When I was a student, there was Columbine, which was supposed to change everything. As a first-year teacher, I saw my co-teacher’s grief as she watched the news unfold from her hometown of Newtown. We all were shocked. Horrified. Disgusted. This must be the lowest possible moment.

Only two short weeks later the threat came to my school. A message scrawled in a boy’s room stall: “One o’clock, tomorrow.” Few students came to school that day; teachers were there as were many armed police officers. At exactly one o’clock, the fire alarm went off. My mentor teacher and I exchanged glances, this is not good. I looked to follow his lead; we both were scared. It was a moment with no right answers. There was no “right” thing to do. Some teachers let the students outside while others locked down their classrooms and hid in the corner. My mentor and I ran towards the exit and ushered students back inside, fearing a shooter outside the building.

False alarm. An accident at the exact worst time. It was the scariest moment of my life. And I don’t know if the next one will be for real.

This week in Florida we had another disaster. Another crisis that shouldn’t have been. Another video of terrified children that shouldn’t have to be on the news. Another set of brave teachers and staff members laying down their lives for students. Another picture of horror that shouldn’t be engraved in our minds forever. Another avoidable tragedy.

The reactions are variations of the same from the last shooting: prayers, thoughts, partisan fighting. An alarming call to arm teachers; a Twitter fight over constitutional rights. A rallying of the tribes.

As we discussed this latest terror, students shared their fears. Some had friends at that Florida high school. Many had been through a false alarm like my own. One student wrote her will during an extended lockdown freshman year. This is what it means to be a student in the class of 2018.

I was supposed to cover Macbeth. But a real tragedy overtook a fictional one. A play of witches and darkness didn’t hold a candle — even a brief one — to the drama of what we face today. And tomorrow.

And tomorrow and tomorrow.

It’s time for all of us to use our teacher voice.

by Shanna Peeples, 2015 National Teacher of the Year, English teacher and doctoral candidate at Harvard

When my school practiced active shooter training, I asked myself: Am I ready to die to protect my students?

Every teacher who will suit up and show up at school today is answering that question by putting their bodies where their beliefs are.

When I witness yet another school shooting, I feel numb, powerless, angry, and depressed. Those feelings are necessary to remind me that I’m a human called to care for younger, more vulnerable humans.

Anyone who teaches will tell you: other people’s children live in our hearts and we love them like they’re our own. Because they are.

And because I love them, I feel a special fear and pain when they ask me: What’s going to happen? Why don’t they stop this?

We are the “they” that has to stop it. How? We stop it with our votes and with our voices.

This has happened over and over, from Sandy Hook to Parkland: teachers putting themselves between a bullet and their students. The best way to honor our colleagues who have made the ultimate sacrifice is to focus on teaching the adults outside our classrooms how to take action.

We are called to take action by actively voting and being brave enough to speak up on behalf of our students and colleagues. As teachers, we are uniquely gifted with the ability to be patient in our explanations and powerful and persuasive in our lessons. It’s time for all of us to use our teacher voice.

I refuse to give in to despair or cynicism. Instead, I remember that my students, former and future, need me to take action. They need me to vote. Yours need you to vote. For those of you who think that voting may not be enough, we need you to run for office. If we cannot protect our children from within the classroom, we must be willing to legislate for them in the halls of power.

There are common sense measures for gun safety we can teach our leaders to understand. We are patient enough to teach and reteach this lesson until they learn that our students’ rights to a safe school overrides the right of those who want weapons of war.

Until you’ve had to fit yourself into a tiny space with 30 silent teenagers to practice hiding from a shooter, it’s hard to think about what guns can do.

So until you’re willing to do that, don’t tell anyone inside a school how this is really all about your right to own a gun instead of their right to live.

Frequent, yes. Normal, no.

by Jason Jaffe, social studies department chair at Glenbard East High School in Lombard, Illinois

I doubt many fellow educators expected to be reviewing violent intruder procedures on the day after Valentine’s Day. Yet, here we are grappling with how to explain to the children and young adults in front of us that just because something happens frequently doesn’t mean that it is normal. Since Columbine, which occurred one year prior to most of this year’s current high school senior class being born, there have been 25 fatal school shootings. Frequent, yes. Normal, no.

Teaching a current events class, my students and I have come to accept that the news and topics we cover aren’t always the most cheerful or optimistic. We’ve covered last year’s natural disasters and the multitude of black individuals’ deaths at the hands of police officers across the country. The most recent school shooting in Florida, however, has yielded the most somber conversations to date.

Undoubtedly, the gravitas with which my high school seniors approached the story and its ongoing developments stem from how particularly close the story hits home. It could have been them. That’s a reality that is not lost on our children. They saw live tweets from students hiding during the shooting. Many of them have watched the Snapchat videos which, in reality, are serving as actual police evidence.

I’m sure that many children around the country spent the end of this week making unusual observations about their surroundings as my students told me they were doing. Normally, students frequently look at the clock in the room waiting for class to end. On Thursday, they were looking at doors and windows, figuring out their escape routes. They were looking at objects in the classrooms to determine how they could barricade the doors or use as a weapon. Again, it’s not normal.

Of course, conversations in my classes invariably converged on one central question: How do we prevent this from happening again? Left unresolved in my classes was any consensus on how much time is needed after such an event before real meaningful debates can start in our country without disrespecting the victims and their families and without seemingly politicizing a tragedy.

I’d encourage fellow educators to model civic engagement by having such conversations and debates in your classes, if appropriate, given the age and maturity of your students. Our kids can handle talking about gun violence. Heck, they’re already living with it.

Our youth are in the middle of a huge mental health crisis

by Kathy Durham, social studies teacher at West Wendover High School in West Wendover, Nevada

A teacher’s epitaph should not read “Died in the line of teaching.” A student’s obituary should not contain the phrase “Gunned down while studying for a chemistry test.”

I began teaching 21 years ago, two years before Columbine. Before that, the most tragic thing that our neighborhood school might endure would be the loss of a student due to suicide or the tragic death of classmates killed in a car accident on weekend date night.

Everything changed with Columbine. I remember the horrifying shock we all felt as teachers. How could a sacred place, a school, become the site of such violence and evil? And even worse to have that violence perpetrated by one of your own.

At the time we all believed that this was just a tragic but isolated event. Certainly one that would never be repeated, let alone become commonplace. Yet, here we are today. Yes, we are still just as horrified, but less and less shocked. We used to say, “Never here,” but now we chatter quietly about who we think is capable of doing it at our school.

At first with each and every new “Columbine” we would sit and have the discussions with our kids. We would begin by telling them, “You’re are safe,” asking if anyone needed to talk, did they want to share their feelings and, of course, emphasizing that if they knew of anyone who might be thinking about doing harm, say something. They were emotional conversations, then afterwards teachers would gather in the hallways, in the office or faculty room, consoling and reassuring one another.

Now, we’ve grown so accustomed to news of “another school shooting” that we merely shake our heads and say WTF, and breathe a sigh of relief that it wasn’t us.

Kids will come down the hall and ask if we heard about the shooting, or ask us if it is true, but not with any real sense of fear or surprise. It’s a just-a-matter-of-fact kind of inquiry. When we confirm the story, they too shake their heads, look at their friends, say WTF and then turn to their phones and continue down the hall.

Meanwhile across the country another teen sits alone in his room, surfing the web, posting videos, writing in a journal, making plans and listing names. And he too, (yes, most likely a male) will soon be the next headline.

Teachers see the lives their students live, and though there are details we sometimes aren’t aware of, we know our kids. As teachers we know this: Our youth are in the middle of a huge mental health crisis. I cannot say enough about the pressures and dangers that social media plays in this crisis. One that dictates to our youth the standards by which they should live and will be judged. The temptations that they face, the ability to bully or be bullied anonymously online are overwhelming.

Yet we have decided as a society the convenience of constant connectivity to our social circles and information world outweighs the risk of it ending up in the hands of unattended children. App developers target our youth with programs that are intended to hide their activities from their parents. Content-hiding apps in the hands of an adolescent child striving to fit into the teenage social structure — what could possibly go wrong in that scenario? As a result, parents must be much more vigilant in monitoring their children’s online lives, but most aren’t.

Schools, whether we want to admit it or not, play a vital role in raising the children in our communities. We take them in at the beginning of each day, we break bread with them during breakfast and lunch.

Most kids will spend more time during the day with us teachers than with their own parent. As a result, whether it is our job or not, whether society wants us to or not, educators will bear a large responsibility in helping to address this crisis.

Unfortunately, because adequate funding for education doesn’t seem to be in the political conversation, schools will be understaffed and teachers ill-equipped to address the issues. That unattended kid with unfettered access to the internet, who fell through the cracks socially, emotionally and academically, will show up to his school one day. Another headline. I just keep praying it will never be mine.

We’re far past the point where thoughts and prayers are enough

by Ryan Werenka, social studies department head at Troy High School in Troy, Michigan

On Feb. 14, my school held a Code Red drill to simulate an emergency, such as a school shooting.

It’s unfortunate that we have to drill for this type of event, and it’s sad that students no longer take this type of drill seriously. I had to repeatedly remind the students in my classroom to be quiet. What happened at Stoneman Douglas High School on that very day is another sad reminder of the world we’re living in and the new reality that we cannot guarantee the safety of our children even in safe havens like school.

I have no doubt that the thoughts and prayers from public officials directed to the students, teachers and families of Parkland, Florida, are heartfelt and sincere. Just as the thoughts and prayers from public officials directed to Littleton, Colorado, and Newtown, Connecticut, were heartfelt and sincere. But I think we’re far past the point where thoughts and prayers are enough.

My question to Congress, President Trump, governors and state legislatures is: What more has to happen before you take some sort of action to protect America’s children? Your collective inaction on school shootings is offensive. You were elected to represent the people, not special interests or your campaign donors. I refuse to believe that you cannot get in a room with credible experts and craft common sense legislation that will address school shootings and protect America’s children.

Since common sense seems to be in short supply when it comes to government, let me take this opportunity to call on Congress and President Trump to form a blue ribbon commission of teachers, students, parents and school administrators and let them do your job for you. Perhaps unelected citizens can demonstrate the courage to make policy on school shootings that you seem to lack. We can pull people from every region and demographic so that solutions are credible and equitable. The growing apathy on this issue puts our children at risk and your inability to address school shootings without any meaningful legislation is shameful.

Yes, some of you may lose campaign contributions, some of you will lose votes and some of you may even lose your jobs, but you’ll be able to sleep at night acting, as you finally act like true public servants.

My students want answers, and they want to solve problems

by David Olson, social studies teacher at James Madison Memorial High School in Madison, Wisconsin

On April 20, 1999, I was a high school junior. It was a Tuesday, and I spent that afternoon competing with my teammates at a speech tournament in suburban Minneapolis. In between rounds, we watched cable news repeat an endless loop of high schoolers filing out of a school and consoling each other after two teenage gunmen killed 13 people at Columbine High School in Colorado.

I remember talking about the Columbine massacre with friends and teachers in the immediate aftermath, and the conversation continued for months and years after. Things changed. High schools secured entrances, established security protocols and instituted Code Red drills. The event was as much a call to action as it was a blow to the soul.

On Thursday, I started my classes like I do nearly every day, by asking, “What’s going on in the world? What do we need to know?”

We started our “Parkland” conversation, but for these students, born in the years immediately following Columbine, their experiences won’t mirror mine.

They had information I didn’t. Something new. Something just reported. More than once, I asked students for a source. We pieced together the events of the previous day, and added to the picture as the day wore on. By 6th period, we had the names of the victims. One student cried as we looked at the pictures.

As a social studies teacher, and one who teaches classes like criminal justice and AP government, my students depend on me for an explanation. When a local robbery occurs or the federal government shuts down, students find me in my classroom or the hallway, and they want answers. We’ve already addressed several mass shootings this school year, and the public debates over security protocols, gun control or mental health treatments have not yielded any results.

Recent history suggests that my students will witness more massacres, but very few changes. They want answers and want to solve problems. On a day like today, I have to have faith that my students can do just that.

Let’s listen to the kids today

by Rusul Alrubail, literacy educator and founder of The Writing Project in Toronto, Canada

My first memory of school shootings in the news was after the Columbine massacre. I was in high school in Toronto, and hearing about the events that occurred during the shooting was very frightening and surreal. School shootings are a rarity in Canada, but they do happen. One of the thoughts that stuck with my me is that the kids who did the shootings did not have many friends and were isolated from their peers.

After hearing about the recent school shooting, my first thought was: Who did it? And how must my teacher friends feel? I needed to know if they were okay.

My friend Christie Nold, a 6th grade public school teacher from Vermont, told me that she felt complete sadness when she first heard the news. “I remember arriving home after a particularly wonderful day with my students. I had turned off the radio in my car, so it wasn’t until I opened Twitter that I saw the news.”

Christie, like many of us, saw the videos of desks and chairs, strewn around the classrooms, and the symbolism was not lost on her: this could’ve been her classroom. “We’ve lived through so many horrific acts of violence in our schools that Marjory Stoneman Douglas becomes Columbine becomes Sandy Hook.”

We should all ask what it must feel like for teachers to talk with their students after a school shooting. In her advisory, Christie shared how so many of her students wanted to know why. They questioned whether the students who committed the act felt unsupported or uncared for. And they shared their own stories of feeling uncared for.

Creating a space where students can just be who they are and express how they feel sounds very simple, but it’s often hard to do. It requires time, commitment, patience and a lot of listening. Let’s listen to the kids today. Listen to them carefully, intently, with empathy. Let’s listen to them in order to understand them, rather than to reply to them. Let’s listen as if their words can change the world.

Popular News

Current News

Manufacturing

Collaboratively administrate empowered markets via plug-and-play networks. Dynamically procrastinate B2C users after installed base benefits. Dramatically visualize customer directed convergence without

Collaboratively administrate empowered markets via plug-and-play networks. Dynamically procrastinate B2C users after installed base benefits. Dramatically visualize customer directed convergence without revolutionary ROI.

About Us

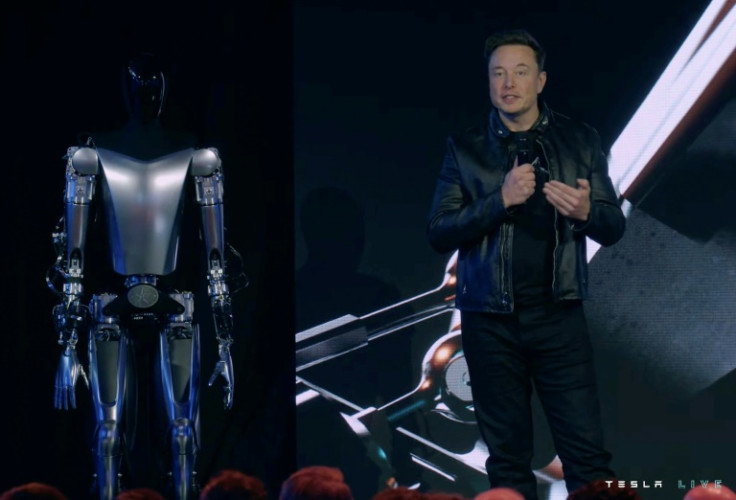

Tech Photos